For a brief moment, these joyous sounds succeed in softening the harsh living conditions faced by the over one million residents of the world’s largest refugee camp.

Described as the most persecuted community globally, the Rohingya Muslim refugees in Bangladesh may now be among the most neglected populations worldwide, eight years after being violently forced from their homes in neighboring Myanmar by a predominantly Buddhist military regime.

“Cox’s Bazar is the frontline for witnessing the impact of budget cutbacks on desperately needy populations,” UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres remarked during a visit to the sprawling camps in May.

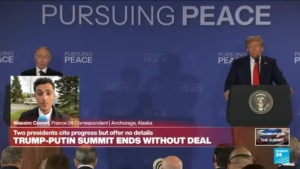

The UN chief’s visit came in the wake of United States President Donald Trump’s drastic reductions to the US Agency for International Development (USAID), which has stalled several crucial projects within the camps. Additionally, the United Kingdom has announced cuts to foreign aid to boost defense spending.

The healthcare in the camps has been severely affected by the sharp blows to international aid.

‘They call me “langhra” (lame)’

Seated outside his makeshift bamboo hut, Jahid Alam shared with Al Jazeera how, prior to becoming a refugee, he worked as a farmer and fisherman in the Napura region of his native Myanmar. It was in 2016 when he first noticed his leg swelling without apparent reason.

“I was working on my farm and suddenly felt an intense urge to scratch my left leg,” Alam said. “It soon turned red and began swelling. I rushed home to apply ice, but it didn’t help.”

A doctor from a local clinic prescribed an ointment, but the itch and swelling persisted.

He soon found standing or walking difficult, unable to continue working and became dependent on his family.

A year later, when Myanmar’s military began burning down Rohingya homes in his village and torturing the women, he resolved to send his family to Bangladesh for safety.

Alam stayed back to care for the cows on his land. However, the military soon forced him to leave and join his family in neighboring Bangladesh.

The 53-year-old has been treated by Doctors Without Borders, or Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), in the Kutupalong area of Cox’s Bazar since his arrival. However, amputation of his leg appears imminent. While some physicians suggest he may have Elephantiasis – an infection causing limb enlargement and swelling – a definitive diagnosis remains elusive.

Along with the disease, Alam contends with stigma due to his disability.

“They call me ‘langhra’ (lame) seeing that I cannot walk properly, he said.

But he adds: “If God has inflicted me with this disease and disability, He has also given me the chance to come to this camp and try to recover. In the near future, I am confident that I can begin a new and better life.”

‘The word “Amma” gives me hope’

Seated in a dimly lit room in a small hut about a 10-minute walk from Alam’s shelter, Jahena Begum harbors hopes that aid organizations will continue supporting the camps, especially for individuals with disabilities.

Her daughter, Sumaiya Akter, 23 years old, and her sons, Harez, 19, and Ayas, 21, are blind and suffer from cognitive disabilities that prevent them from speaking clearly. They live largely unaware of their environment.

“Their vision began to fade as they entered their teenage years,” Begum explains.

“Watching was incredibly hard, and healthcare facilities in Myanmar were unable to help,” mentioned the 50-year-old mother as she caressed her daughter’s leg.

The young girl chuckled, unaware of what was happening around her.

Begum’s family made their way to Cox’s Bazar about nine months ago following their house being burned down by Myanmar’s military.

“We arrived at the camps with the help of relatives. But life has been exceedingly hard for me,” said Begum, mentioning her solitary efforts in raising her children since her husband’s passing eight years ago.

Doctors from MSF have provided her children with glasses and have initiated scans to comprehend the underlying cause of their disability.

“Currently, they express everything by making sounds. But the one word they say, ‘Amma’, which means mother, shows me that they at least recognize me,” Begum said.

“The word ‘Amma’ gives me hope and strength to keep trying to treat them. I wish for a better future for my children.”

‘The pain isn’t just physical – it’s emotional’

Clad in a blue and pink striped collared shirt and a striped brown longyi – the cloth worn around the waist by men and women in Myanmar – Anowar Shah recounted his escape from Myanmar and the loss of a limb to a mine blast.

Shah shared that he was gathering firewood in his hometown of Labada Prian Chey, Myanmar, when his leg was blown off by a landmine last year.

According to a 2024 UN report, Myanmar is among the world’s deadliest countries for landmine and unexploded ordnance casualties, with over 1,000 victims recorded in 2023 alone – more than in any other country.

“Those were the most painful days of my life,” stated 25-year-old Shah, who now uses crutches to get around.

“Losing my leg shattered everything. I transitioned from someone providing for and protecting others, to someone dependent on others to get through each day. I can’t move freely, can’t work, can’t even complete simple tasks independently,” he lamented.

“I feel like I’ve become a burden to those I love. The pain isn’t just physical – it’s emotional, it’s deep. I constantly ask myself, ‘Why did this happen to me?’”

More than 30 refugees in the camps in Bangladesh have lost limbs in landmine explosions, leaving them disabled and reliant on others.

All parties to the armed conflict in Myanmar have used landmines to some extent, stated John Quinley, director of the rights organization Fortify Rights, located in Myanmar.

“We are aware that the Myanmar junta has been using landmines for many years to fortify their bases. They also lay them in civilian areas surrounding villages and towns that they have occupied before retreat,” he stated to Al Jazeera.

Abdul Hashim, 25, who lives in Camp 21 in Cox’s Bazar, explained how stepping on a landmine in February 2024 “radically changed his life”.

“I have become reliant on others for even the simplest daily tasks. Once an active contributor to my family, I now feel like a burden,” he said.

Upon arriving in the camp, Hashim joined a rehabilitation program at the Turkish Field Hospital, where he receives medication and physical rehabilitation that includes balance exercises, stump care, and hygiene education.

He has also been evaluated for a prosthetic limb, which currently costs approximately 50,000 Bangladeshi Taka ($412). The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade of Australia covers the expense for such limbs.

“Despite the trauma and hardship, I hold onto some hope. I dream of soon receiving a prosthetic leg which would allow me to regain some independence and find work to support my family,” Hashim said.

Thus far, 14 prosthetic limbs have been distributed and fitted for camp inhabitants by the aid organization Humanity & Inclusion, which has expertise in producing the limbs in orthotic workshops outside the refugee camps.

Both Hashim and Shah are part of the organization’s rehabilitation program, which is providing gait training to help them adapt to the future use of prosthetic limbs.

Tough decisions for aid workers

As aid workers strive to ensure refugees in the camps are well-supported and can improve their lives after fleeing persecution, they’re now facing tough decisions due to cuts in foreign aid.

A healthcare worker from Bangladesh, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of impacting future aid from the US, told Al Jazeera, “We are having to decide between providing food, education, and healthcare due to aid cuts.”

Quinley from Fortify Rights highlighted that while there are significant funding gaps due to aid cuts, the Rohingya refugee response shouldn’t solely rely on any single government and is a collective regional responsibility.

“There needs to be a regional response, especially for countries in Southeast Asia, to provide funding,” he said.

“Countries associated with the OIC (Organisation of Islamic Cooperation) in the Middle East could also offer significantly more substantial support,” he added.

He also recommended partnering with local humanitarian organizations, “whether they are Bangladeshi nationals or Rohingya refugee groups themselves,” since they understand how best to assist their communities.

“Their capacity to reach those in need is paramount, and they should be supported by governments worldwide,” he stressed.

For the estimated one million refugees in Cox’s Bazar, urgent support is required at a time when funds are increasingly scarce.

According to a Joint Response Plan developed for the Rohingya, in 2024, only 30 percent of the needed $852.4m in funding was received by the refugees.

As of May 2025, against an overall appeal for $934.5m for the refugees, only 15 percent received funding.

Cutting aid budgets for the camps, said Blandine Bouniol, deputy director of advocacy at Humanity & Inclusion humanitarian group, is a “short-sighted policy” that will “devastatingly impact people.”