<

div aria-live=”polite” aria-atomic=”true”>

Seongam Island, South Korea – Two men stand at the entrance to a forest surrounded by tall pine trees on an island south of the capital Seoul.

In the middle of the forest, there is a large clearing and an excavation site.

The words written on a safety notice reveal what this forest hides: “Seongam Academy Graveyard Recovery Operation”.

Chun Jong-soo and Pak Sung-ki were just boys when they were among thousands cleared off the streets by South Korean authorities for alleged vagrancy, and held for years as inmates at institutions like Seongam Academy.

Seongam island was only accessible by boat when Chun and Pak were first detained in 1965 and 1980, respectively.

Fighting to control his trembling voice, Chun says he remembers the burial site now being excavated here. He was among the young detainees forced to bury the bodies of his fellow inmates who died trying to escape. Chun told Al Jazeera how they would recover bodies that washed up on the island’s shores and bury them at this forest cemetery.

“It was meant to show us the consequences of trying to escape,” Chun said.

“Memories of seeing those bodies still haunt me in my sleep.”

Hundreds and possibly thousands died amid the forced labour, violence, and sexual abuse that prevailed in the group homes and detention centres – like the Seongam Academy – that were established across South Korea during the country’s decades of heavy-handed rule from the 1960s through to the 1980s.

Among the most notorious was “Brothers Home”, a so-called welfare centre that was once located in the southern port city of Busan, where thousands were enslaved and abused in a state-sponsored programme to punish vagrants and clear the homeless from South Korea’s streets.

While police did most of the seizures, Brothers Home employees were also allowed to patrol the city in trucks to do the kidnapping themselves. Children, people with disabilities, and the homeless were rounded up, detained and forced to work at the home where survivors recounted witnessing people beaten to death by staff or left to die from injuries.

‘Real hell’ v TV drama

The existence of these brutal institutions in South Korea has come to wider attention as Netflix’s Squid Game gains global attention.

Season two of the South Korean drama kicked off late last year by racking up the largest audience ever for the debut of a TV series by the online streaming service.

In just three days, the dystopian drama about down-on-their-luck South Koreans playing life-or-death games for a jackpot prize of millions amassed 68 million views.

Across social media, the Squid Game hype has been prompted by reports the show was based on the real-life horrors that took place at such places as Brothers Home and Seongam Academy.

Images purportedly of the Brothers Home have gone viral online, showing eerily similar interiors to the colourful, Escher-esque facility depicted in Squid Game where people compete at children’s games and the losers are killed violently.

One Facebook user with more than a million followers shared images of dimly-lit, derelict hallways painted in the TV show’s iconic pink and green. Only later were the photos identified as fakes, generated by AI tools online, according to fact-checking organisations.

South Koreans have also criticised comparisons with the TV show, some saying Brothers Home was worse in ways than the fictional island prison of Netflix fame.

“Fiction can’t keep up with the horrors of reality,” wrote one South Korean social media user, who said life was “real hell” in the homes compared with that in the TV show game.

In 2022, South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, an independent investigative body, confirmed that 657 people died at Brothers Home in Busan between 1975 and 1986. Testimonies from survivors of the home recounted horrific conditions that included intense forced labour, physical assault, systemic sexual abuse and pervasive cruel and degrading treatment.

“On paper, these facilities were established out of the need to provide relief to impoverished welfare recipients,” said Ha Geum-chul, an investigator for the commission.

Hidden was the true function of such centres, Ha said.

“Contrary to their stated goals, the forced detention of welfare recipients against their will, human rights abuses, and forced labour in the centres were vastly problematic,” he said.

According to Ha, such centres were part of a “unified system of nationwide vagrancy enforcement and detainee management” established by the Ministry of Interior and enforced by police officers who earned “job rating” points for each child apprehended and admitted.

“General arrests gave officers up to three points while an admittance to Brothers Home was worth five points. This suggests that police officers performed excessive crackdowns to improve their job performances,” Ha said.

‘Escape this place at all costs’

Visiting the site of the Seongam Academy with Al Jazeera, Chun told how he was captured by authorities while hanging around Seoul’s train station when he was just 11 years old.

“I was on my way to my sister’s house when government officials took me in their van. Afterwards, I rode a boat with 40 other captured inmates when we entered the island,” he said.

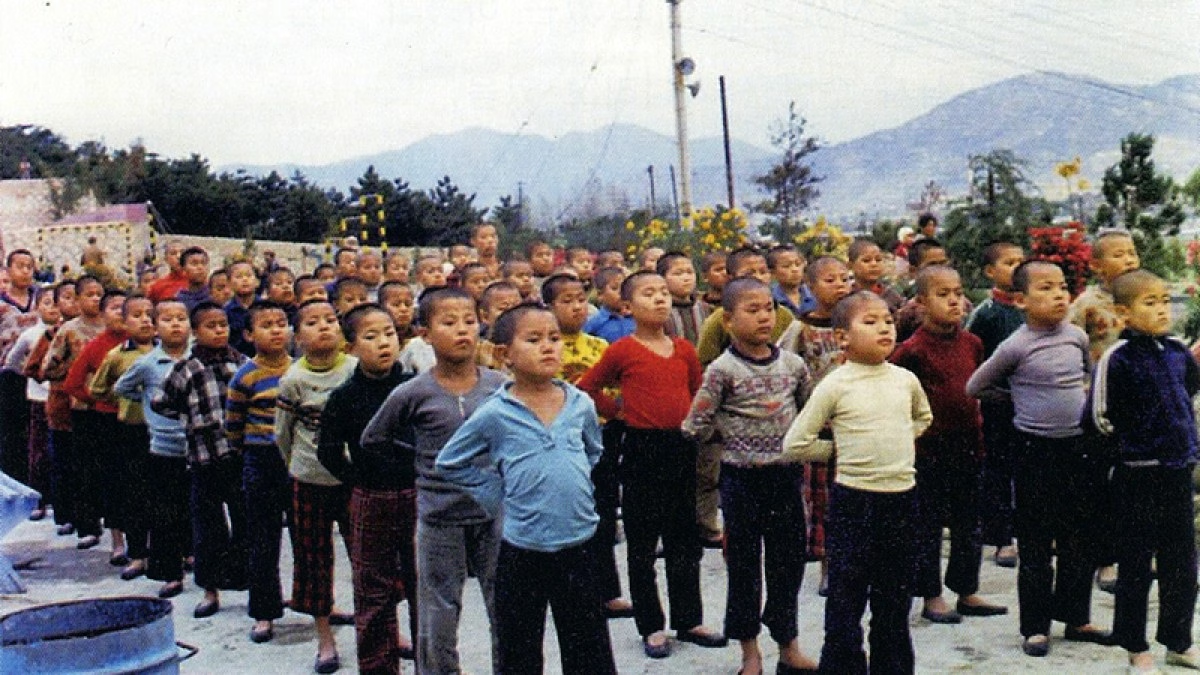

“Every day, we woke up at 6am, assembled in front of the grounds, and worked in the fields all day. They would only give us lunch after we hauled 25kg (55lbs) of rice,” he recounted. “Even then, lunch only consisted of a fistful amount of rice and salted shrimp.”

As for what he remembers most about his nine years at the so-called welfare centre, Chun says everyone was beaten daily for the smallest of offences, such as being too chatty.

“They just couldn’t bear to let us be kids,” said Chun, who is now 69 years old.

“They made us use our excrement as fertiliser and didn’t even care if someone collapsed from heatstroke. That’s why so many of us dreamed to escape this place at all costs,” he said.

Inmates would team up in small groups and devise plans to flee. The young boys would practise swimming in a reservoir on the island in the hope of one day making it to the mainland under their own strength across the sea.

Many would die trying to undertake the long swim to the shores of Incheon, or the infamous swamps on the island would drown them in their depths before they got very far, Chun said.

Chun told how his wife often asked why he still screams in his sleep.

“The trauma is something that I will have to carry with me until I die,” he said.

<

h2 id=”a-permanent-dent-in-me”>‘A permanent dent in me’

Source: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/3/1/versions-of-hell-squid-game-and-s-koreas-historical-homeless-centres?traffic_source=rss