Ask your average German what they associate with the name Rudolf Steiner and they may well list off a string of things, from natural cosmetics brand Weleda to Demeter organic food products to the alternative school in their town. The name will at least ring a bell. Ask a non-German the same thing, and chances are they’ll just scratch their heads. Yet while Steiner himself may not be well-known, his ideas have certainly had global impact, especially in the field of education.

Steiner opened the first Waldorf school in 1919, and, 100 years after his death (on March 30, 2025), there are some 3,205 Waldorf kindergartens and schools in 75 countries around the world, from Mexico to Tanzania and China. Despite this reach, even parents whose kids attend Waldorf schools may not be that familiar with their founder and his ideas.

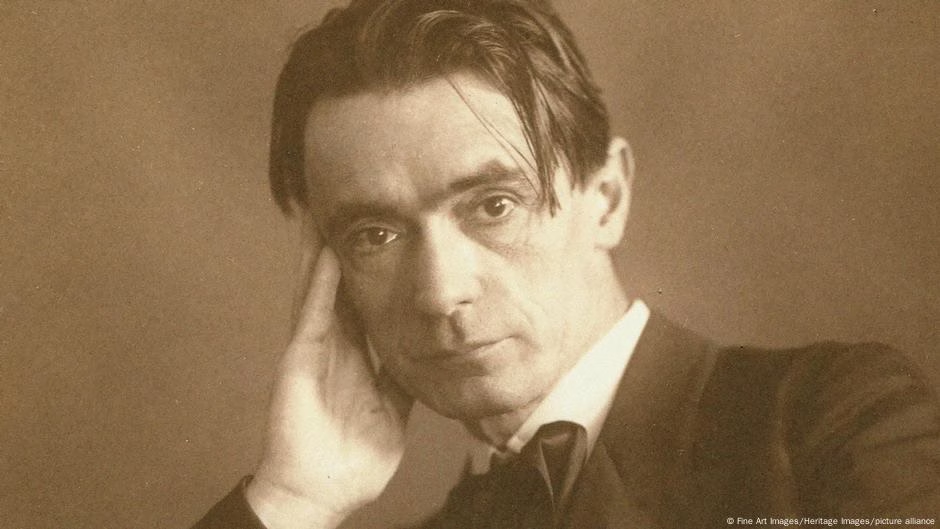

Rudolf Steiner: A ‘magpie’ thinker

Rudolf Steiner was born on February 25, 1861, in what is now Croatia. From a young age, he claimed to have clairvoyant visions, such as visitations from dead relatives. Such experiences significantly influenced his later philosophies invoking an unseen yet real and accessible spiritual world. As a student in his early 20s, Steiner was given the opportunity to edit Goethe’s scientific writings. He found himself drawn to the German polymath’s spiritual idea of nature. He was also an early admirer of Friedrich Nietzsche.

Steiner eventually rose to prominence within the theosophy movement, a late 19th-century esoteric and occultist movement involving pantheistic evolution and reincarnation that also fed into his beliefs. Author Gary Lachman, who wrote a popular biography of Steiner, says the spiritual thinker has been described as a magpie.

Steiner called this form “anthroposophy,” taken from the Greek for human (anthropos) and wisdom (sophia). It centers on the idea that a spiritual world exists that is perceivable to humanity through enhanced consciousness and independent thought. According to Steiner, humankind had largely evolved away from accessing this world, but they could relearn to do so again, which would lead to individual and universal well-being and advancement. Despite its odder elements — such as belief in the lost continents of Atlantis and Lemuria, the pairing of the biblical figure of Lucifer with the Zoroastrian figure Ahriman, and the incorporation of karma and reincarnation within a Christian framework — Steiner’s anthroposophy proved highly attractive.

“I think he offered people a sense of meaning, purpose,” Lachman explained. “We can look at it and think it all sounds rather really wacky … Put that aside and he’s basically trying to awaken and acknowledge human beings and their entire nature.” People flocked to Steiner’s movement, and he became widely popular. Over the years, Steiner and his followers applied his ideas to architecture, dance, medicine (in the form of alternative healing practices), political theory, banking and biodynamic agriculture, an early form of organic agriculture that involves a mystical approach. He was best-known for influencing education in the form of Waldorf schools, which emphasize a non-traditional creative curriculum over standard subjects like literacy and math.

Progressive, antisemitic and racist or both?

Steiner was both progressive and held views that are today considered antisemitic and racist. While he railed against popular antisemitism, he also described Judaism as “a mistake in world history” and called for Jews to assimilate to the extent that they would cease to be Jewish. Historian Peter Staudenmaier, who has written on Steiner’s relationship to antisemitism and racism, says he can’t be pinned down in one category due to the complexity and evolving nature of his thoughts.

Anthroposophy under the Nazis

Steiner’s contradictory views meant that anthroposophy was both attractive and a threat to the Nazi movement. Unlike many other contemporary esoteric movements that failed to outlive their leader, anthroposophy remained strong after Steiner’s death in 1925 thanks to his charisma and significant number of dedicated adherents. His practical ideas regarding biodynamic agriculture, for example, was embraced by some Nazi officials, as was his Germano-centric view of human evolution. Yet other Nazi officials saw in anthroposophy a dangerous movement and ideological threat to the party.

Steiner’s legacy today

As the 100th anniversary of Steiner’s death on March 30, 1925, rolls around, some anthroposophical organizations have begun to acknowledge and grapple with the discriminatory elements of Steiner’s work and writings — even as they argue these are often misunderstood and don’t detract from his universal message.

Nevertheless, Steiner remains a household name in Germany and anthroposophy remains a global, if rather niche movement. There are 36 national anthroposophical societies around the world comprised of roughly 42,000 members.

Source: https://www.dw.com/en/waldorf-schools-and-weleda-founder-who-was-rudolf-steiner-really/a-71920999?maca=en-rss-en-all-1573-rdf